Having taught college art courses for 45 years, I have had the privilege to help shape the minds of many aspiring artists. One of the first things I told my students at the beginning of their studies was that good art always has two components. The first is technique [craft], and the second is the idea [content]. If all someone has is technique without an idea, one becomes a dead technician. If one has a great idea but poor technical skills, no one will take the idea seriously.

So as they developed as an artist, care had to be given to both areas. Technique is fairly easy to teach through much practice. I could teach anyone to draw what they saw. But once that skill was acquired, the hard part, idea, was another story, and this was where my students struggled most.

So the question is: Where do ideas come from?

The purpose of this post is to discover the sources of our inspiration and imagination. If one looks at the roots of the word inspiration, he will discover that it means “from beyond.” This comes from the Greeks who believed that it was the “kiss of the muse” that was the spark that set afire the artist’s fantasy. For those not familiar with Greek mythology, the muse was a goddess of inspiration. Plato said, “Poets do not write by wisdom, but by a kind of genius and inspiration.” They felt a direct divination occurred while in a creative trance. Coming from beyond, like the Hebrew prophets. This is a romantic approach to ideas.

When past creatives were asked where their ideas came from, the answers varied considerably. Beethoven said he couldn’t say. The composer Weber said it was a gift from above. Anton Bruckner, when asked by an admiring pupil, “How did you find the beautiful theme of your 7th symphony?” replied, “The good Lord sent it.” Mozart received his inspiration often while walking through the woods. He said as he walked, a melody simply came to him, complete. When he got home, he just wrote it down. Then the next day, during a walk, the counterpart would come to him, intact, and again, he just wrote it down when his walk was over. That is why there were never any corrections in his sheet music—because he didn’t need to change anything. Yet with Beethoven, there were so many corrections that the original sheet music often had holes in it.

Bach approached his musical scores through a formula. Ansel Adams, the great photographer, said he got his inspiration by taking 1,000 pictures to find one good one—hardly inspirational. Cezanne struggled and struggled and was never satisfied, whereas Manet and the Pointillist Seurat both believed art could be made through strict formulas. What we can conclude from this is that inspiration and ideas come in many packages.

Art is a craft as well as an art. Craft can be the creative source. But inspiration and craft should not be thought of as separate entities. Art never stems exclusively from either inspiration or craft alone. Craft is unthinkable without inspiration [the dead technician], and inspiration without craft can never be expressed fully.

We will discover that there are two views on this subject. The first is the mystical view of inspiration, which is a romantic idea. Prime examples of this in art would be William Blake and Michelangelo. The second is the rational, which emphasizes craft [technique]. This is the Classical approach exemplified by the Neo-Classical movement of the mid-1700s in France under Jacque Louise David who introduced the idea of Academic Art, which was a belief that art could be taught through rules and formulas. The Classical approach to inspiration is driven by logic. The mystical approach is driven by passion and intuition, or the ‘heart.’ The Romantic movement in art had an expression to counter the Classical approach that said, “The heart has its reasons that reason does not know.” The ideal is a blend of inspiration and craft.

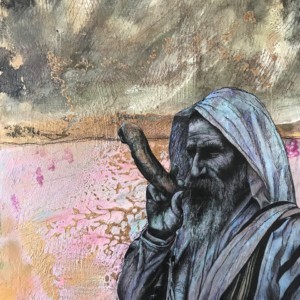

Announcing the King of Glory by Gary Wilson

The beginnings of inspiration are traced back to the process of birth itself. The parents, their genes, family heredity, and traits are passed on to the newborn. I had a woman in my ceramics class at the college who had never done anything in art. Yet when she began to work with the clay, she began making incredible stylized figurative sculptures. I couldn’t believe it, and neither could she. Then, during a semester break, she went to Italy to meet some family that she knew nothing about. While there, she told them about her experience with sculpting and her confusion about how she could make these. She discovered that three generations back, she had a great, great, great grandfather and other family members that were renowned sculptors in their day. Genetics!

This ability to imagine is shared by everyone, whether they develop it or not. God gives ability at birth, for He is present at everyone’s conception. The Annunciation of the angel in Luke 1:28 is spoken to all, “Hail, you are favored of the Lord, and this is what you shall be…” This is the role of nature.

Next, one’s childhood helps to shape one’s creative imagination, whether to encourage or discourage the natural growth of creative imagination. Artists are sometimes born into artistic families, which helps to set their direction, but artists are also born into non-artistic families and must find their own way—even finding their own way, however, becomes part of the creative process.

Picasso had a painter father who taught the young Picasso all he knew about painting as did Andrew Wyeth. But Van Gogh and Michelangelo were denied the encouragement of their parents. Mozart was encouraged by his parents to become a musician and composer, but Handel’s parents did everything they could to discourage him. This falls under the category of nurture.

As the maturity of an adult creator develops, the imaginative ability is shaped in the subconscious by the imaginative works of others. The student sees and hears others’ work, and his senses are encouraged to develop by their exposure to this work by artists who awaken in them admiration and desire. It is at this level that the developing imagination becomes part of the age or period in which each artist finds him or herself.

Whether the artist follows the prevailing style or chooses to lead the way to a new style is part of the response of the maturing imagination. But in the early stages, the following usually precedes the leading. All artists begin by imitating a prevailing style. Some go on imitating and never break away yet still accomplish tremendous heights of achievement. A few leave the accepted mode and blaze a new style which in turn gives leadership to others.

Rubens broke away from the style of his teacher, but Snyder, his pupil, followed closely in the style of Rubens. Both created works of value. Both contributed to the enrichment of the arts. Our age would tend to worship the trailblazer but downgrade the follower. But this is an artificial judgment that history does not support. No artist can actually claim to have been self-taught because all imagination stands on the shoulders of someone else’s imagination. Even the trailblazer has to begin by being a follower.

Inspiration in this sense comes from the outside, through others, sometimes in the form of homages. Artists become attached to another artist or a specific work and do themes and variations on that work. Picasso did hundreds of re-paintings based on Velasquez, Manet, Delacroix, and Vermeer. And this is nothing new relative to our own century. Titian copied, copied, copied, and the Renaissance is full of paintings that were “borrowed” from each other.

When an artist thinks they are pure originators, they are arrogant and deceived by the most treacherous of deceptions—self-deception. Inspiration is not arrived at by taking giant steps. Rather, inspiration is a flowing river, and we are carried along, for a time, by its current.

Inspiration is, at the same time, from within and from without. From within in the form of one’s equipment of parental genes and the developing personal abilities. From without in the form of the style of one’s developing age and peers. The oracle speaks from within through whispering tones, and the voice shouts from the outside in stylistic announcements.

So the next time you hear someone simplistically say, “God gave me this idea,” realize that there is much more to inspiration than that. Like many of the people mentioned above, we realize that our ideas feel like they are from beyond at times. We can’t often explain them. But there is more of you in the mysterious ideas than you realize.

God never erases us. He works through us by allowing us to share in His imagination. Your product will always carry your personality as well as God’s. That is why the four Gospels are so different. God allowed the personalities of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John to remain even though the Word was inspired by God. We get to share a taste of His glory. God is interested in what we do and is delighted to partner with us.

Featured and In-Text Images painted by Gary Wilson

Comments are closed.